I have written about the restriction on ‘gatherings’ in Reg 7 of The Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (England) (Amendment) (No. 3) Regulations 2020 previously, and submitted evidence to the JCHR on it as well. The focus of most previous commentary has been on Reg 6, imposing what is usually referred to as a ‘lockdown’, prohibiting us (in England at least) from leaving our homes except with good reason, ’reasonable excuse’. There was little need to dissect Reg 7, or for it to be applied, since we were all, in general terms at least, forbidden from being outside. That, of course, is rather a simplification: Reg 6 identified many instances of what would be considered a ‘reasonable excuse’, as well as the general catch-all. The harshness of the general prohibition was ameliorated too by relaxation on 13 May, by allowing us to take exercise and visit public open air spaces with someone else.

Today, changes were made (subject to Parliamentary approval within 28 days) the result of which is to place Reg 7 firmly in the spotlight, and very much to relegate Reg 6 to a bit part. We, in England at least, are now able to leave our homes; the restriction now is that we must not stay overnight somewhere else, unless we have a reasonable excuse. That list remains broadly the same, but with, for example, the addition of exemptions for ‘elite athletes’ (Reg 6(1)(b)). Instead, the focus – in terms of preventing the spread, and keeping the R number (well) below 1 – is on how gatherings are regulated.

Others have commented on the constitutional dynamics that arise from the way these changes came about: published late on a Sunday afternoon, to come into effect at 11:30 the following day, excluding Parliament from any ex ante scrutiny, using the urgency of the need for the measures, what barrister Tom Hickman QC typified as “abracadabra governance”. I do not propose to add to that, other than to express agreement.

Instead, I want to offer a few thoughts on the new, fleshed-out Reg 7, outlining where it differs from the previous iteration and suggesting what seem to me to be ongoing areas of concern.

Formerly, gatherings of more than two in a public place were prohibited (with attendant criminalisation in Reg 9 and enforcement powers in Reg 8) unless one of four exemptions applied: same household, essential for work purposes, to attend a funeral, or was reasonable necessary to facilitate a house move; to provide care or assistance to a vulnerable person; to provide emergency assistance; or to participate in legal proceedings/fulfil a legal obligation. The new prohibition retains some elements of that. The list of permitted reasons to exceed the restriction on gatherings is exhaustive; there is no general caveat of “reasonable excuse” with examples of what might constitute it. Since Reg 7 will be doing much more of the legwork, replacing in effect the general prohibition on what was old Reg 6 – which was drafted in that manner – this is surprising. However, while the prohibition is absolute subject to those listed exceptions, Reg 9 which creates the offence of contravening the prohibition on gathering does include a ‘reasonable excuse’ defence. This offers the possibility of seeking to argue that the protected Convention right of freedom of assembly/freedom of speech (in ECHR Arts 11 and 10 respectively) – effectively a right to protest – constitutes the reasonable excuse for gathering. I made this point in my evidence to the JCHR (para 10). Another route by which to render the Regulations ECHR-compliant would be to argue that the scope of the term “gathering” should be read (utilising s.3 of the HRA) so as to exclude gatherings that would be protected by Arts 10/11 as expressive assemblies. Those two routes should avoid the alternative (should a case be brought) of declaring Reg 7 incompatible with those two protected Convention rights. That would mean, since they are contained in secondary legislation, there would be no question of a court “only” declaring them incompatible under s.4 of the HRA; issues of parliamentary sovereignty, at the heart of the s.3/s.4 scheme, do not obtain. Regulation 7 would be susceptible to being struck down, of no effect.

Some of the points I raised in that submission and my earlier blog post have been dealt with, although not necessarily satisfactorily. There is now greater clarity on what constitutes a gathering – a term not generally used previously in domestic legislation, which has favoured the more widely used ‘assembly’. Under the Regulations as amended, a gathering is where two or more ‘are present together in the same place in order to engage in any form of social interaction with each other, or to undertake any activity with each other’. This begs more questions than it forecloses.

- The first “engaging in any form of social interaction with each other” is presumably rendered otiose by the latter – “any activity” must encompass “social interaction”. Why then might the drafter have chosen a specific and a general? I did have a rather detailed, and likely very dull, attempt at an explanation – seeking to draw out subtle differences but in truth I suspect that using two near-synonyms is simply surplusage, belt and braces. The alternatives must be read as interchangeable, with the latter, general ‘undertake’ – to enter/embark upon, to begin – taking precedence over ‘engage’ (to embark on any business’; to enter upon or employ oneself in an action).

(For those interested, I was exploring whether the purposive ‘in order to’ might be disjunctive: gathering is either two or more who are ‘present together in the same place in order to engage in any form of social interaction with each ‘ OR that it is two or more who are ‘present together in the same place to undertake any activity with each other’. The former would imply two (or more) with synchronicity of location and intention i.e. two people together at place X plan/intend/have as their purpose to have some form of social interaction, but are currently doing nothing together. The latter ‘only’ covers those who are together in one place and are actually undertaking an activity with some other person It is hard, in truth, to see what is added by taking such a precursor, inchoate approach to the wording OR, if such an approach is mandated by that strangely but deliberately constructed phrase, then it is overly broad, capturing too many activities and/or allowing too much policing discretion and creating too much uncertainty. The alternative angle I explored was that ‘undertake’ can also mean commit to future action such that a gathering is either two or more who are ‘present together in the same place in order to [so that they may] engage in any form of social interaction with each other OR that it is two or more who are ‘present together in the same place in order [so that they may] undertake [commit to doing] any activity with each other’. Again, it is hard to see what is added by each.)

- Being present together in the same place – might this now include meeting/conversing on-line? If not, why not – is it that the internet is or, or cannot be “a place” (and is either no place, or all places?) There is much written on that to gainsay that approach. In the US, Justice Kennedy described the internet as “the modern public square” (Packingham v North Carolina 137 SCt 1730, 1737 (2017)). Is it that no one is present together – there is always a microsecond (at least) between A posting on say Facebook or Twitter, and B seeing it, or replying, or liking? The matter did not arise under Reg 7 in is first guise, as that only prohibited gatherings in a public place, and so did not bite upon virtual gatherings.

- The definition does not really help us identify what activities might sensibly be prohibited – what is the real target of the new rule? – so that we might avoid doing them. Perhaps, put another way, the word ‘with’ is being asked to do a lot of heavy lifting – if I am at a bus stop, waiting for No.37, and there are six others there too, am I not engaged in the activity of “waiting” with them? Am I not ‘with’ other supporters in the away end at Carrow Road? It would not be a stretch of normal use of English to describe it thus, but to obviate such over-reach (or what we might presume is unintended overreach) does ‘with’ need to encompass some form of agreed activity rather than simply meaning “alongside” or even “near”, some form of active conjoining rather than simply locational co-incidence?

The major change in the Regs is the inclusion now of all places, both public and private. My earlier criticism (JCHR evidence, para 21) – that there was no definition of “public place” – obviously falls by the wayside. The extension probably provides an answer to the question at 2. above since it further goes on to identify the rule as covering (i) public or private indoor places and (ii) public or private outdoor places. In other words, though the internet and a webpage are a place, and a private one at that, they are neither indoors nor outdoors (at least not as defined elsewhere in the Regs). Nonetheless, there are a few concerns.

First, we should note that the prohibition formerly applied only where more than two people gathered in a public place. Now, in indoor public and private places, it covers any gathering of two or more i.e. once I am no longer alone in my house or any other ‘substantially enclosed’ (Reg 7(3)(b)) indoor place. To some extent, this change is simply replicating the previous Reg 6 scheme; while I am no longer barred from leaving my home, I am barred from going into anyone else’s unless say it is for work. The end result is the same – households remain in indoor silos. While previously (subject to the general ban in Reg 6) I could have invited someone into my kitchen or my garden, I can now only invite them into my garden. The rationale is clearly the notion that the risk of spread and infection is far greater inside than outside. It does produce interesting results. As many have noted on Twitter, it still prohibits couples who for a variety of reasons might live in separate households from meeting in the house of one of them and, indeed, prevents two people who are not in the same household (i.e. partners living together) from having sex with each other indoors at least. Though, as one commentator noticed, it does not prevent A inviting B into their home for sex and B paying for it, as that falls within the work exception for A! (NB – I have tried to find out who this was, I read it in passing, but cannot now do so; very happy to attribute). The new rules also produce this counter-intuitive result, one that flies in the face of the health-related purpose that must underpin the Regulations, or their interpretation: up to six people can gather with impunity outside. Strangely, this means that a household of five together can only gather with one other person – hosting a BBQ in the garden for example – but a person living alone person can invite five others; the health risks are very different. The explanation must be the ease and effectiveness of policing and enforcement – in outdoor places, it is simpler to count and see of the gathering numbers more than six, rather than complicated questions about relationships to each other. If the gathering numbers more than six (outdoors), then the (policing) question arises: are you all in the same household? The Regulations say nothing here about onus of proof. It is here that we reach a structural problem with the design of the Regulations.

Regs 6 and 7 do not create offences, or allow for enforcement. They impose requirements of restraint – formerly a prohibition on leaving one’s place of residence, now staying overnight at someone else’s, and on certain gatherings. Reg 9 creates the offence – comprising a reasonable excuse defence for Reg 7, it being absent in the requirement (as I discuss above) and a strict liability offence for Reg 6 but which itself does include it (in both an overarching claw-back, and with over a dozen illustrative examples) so the end result is the same: both offences can only be committed where someone ostensibly in breach does not also have a reasonable excuse. Whether we view “reasonable excuse” as part of the requirement (Reg 6) and thus part of the actus reus or, as with Reg 7, a defence to be raised by the accused matters only in that if it is a defence, some prima facie evidence has to be adduced in order for the matter to be live. The legal burden – proving beyond all reasonable doubt that there someone had no reasonable excuse – remains with the Crown. However, that might not in practice matter very much, because of the way the enforcement power in Reg 8 operates. Much of the policing of the Regulations relies not on formal court processes – charging for one of the various crimes – but through police officers being able to direct someone to return to the place where they live, or remove them there (where the officer considers they are contravening Reg 6) or directing gatherings to disperse, as well as directing people to return to the place where they live or removing them there (where the officer considers they are contravening Reg 7). It is here that the structure matters. Where a reasonable excuse is contained within, or as part of, the definition of the restriction, as it is in Reg 6, then an officer in order to act lawfully must not only consider whether someone is away from the place where they live (old Regs) or staying away overnight but also whether they might have a reasonable excuse. Where the existence of a reasonable excuse is not an integral aspect of the requirement, but only of its criminalisation (in a separate Regulation), they need not consider whether there is a reasonable excuse for the gathering.

To develop this further, even if, as I argued above, exercising my right to protest and assemble peacefully (under Art 11) might constitute a reasonable excuse, there is no need for an officer to consider as part of the process of lawfully directing a gathering to end. (As an aside, and rather technically, there are here issues to be explored around the duty in s.6 of the HRA, on officers not to act or reach decisions which disproportionately restrict those rights, but read in light of the “outcomes are all” approach at the heart of Begum [2006] UKHL 15 alongside, most recently RR v SoS for Work and Pensions [2019] UKSC 52). For those who feel that policing decisions – to remove, and to direct a gathering to end – have wrongly deprived them of their statutorily-guaranteed rights, the solution can only be ex post and to the courts. One final point on this aspect: if today’s changes do herald a shift onto Reg 7 as the linchpin of enforcement, at the expense of Reg 6, we should bear in mind Reg 8(1). This remains unchanged and allows relevant persons, such as police officers, to “take such action as is necessary to enforce any requirement imposed” by Reg 7. There is no such power, with such width, to secure compliance with Reg 6. I would assume that necessary would be read as “proportionate” adopting on very different facts admittedly the approach that the House of Lords took to “necessary” in s.10 of the Contempt of Court Act 1981, where there was a risk to journalistic freedom: Ashworth Security Hospital v MGN Ltd [2002] UKHL 29 [61]-[62].

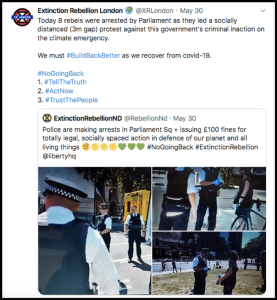

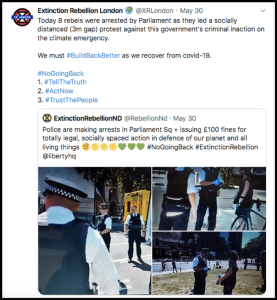

I’d like to conclude with some thoughts on where this change leaves the right to protest in England in light, for example, of arrests made of XR protesters in London over the weekend of 30 May.

While the amendment offers a little more insight into what constitutes a gathering, it fails to resolve the one, critical matter: how close must I be to someone else to be “gathering” with them? This is a point I made in my earlier blog, and submission to the JCHR. In short, the argument I made was that, given these regulations have been made under health prevention legislation, they must be read subject to that, not as public order provisions. From that should follow this conclusion: if I assemble or meet (certainly outdoors) more than 2m from someone else – and certainly if this is not for any great length of time – I am not acting unlawfully, as I am not ‘gathering” within the meaning of that word in the Regulations. Twenty, fifty, one hundred of us all 2m+ apart are not gathering. Such a reading preserves the constitutional value of politically participative protest, over and above (say) the value of social or recreational value of six friends having a BBQ – where, we should note, there is no time limit in the Regulations. Government Guidance, amended to take account of today’s changes, tells us little more, and neither does today’s amended National Police Chief’s Council Guidance Note. Noticeably, they make no reference to protest gatherings, not to any Convention-protection or indeed Convention-impact such as for example (and again noted by many on-line commentators and contributors) the impact on family life of partners in different households not being able to meet. The omission of both is not surprising. However, while we can explain the difference on grounds that bright lines facilitate ease of policing, in order to withstand HRA scrutiny, Government (if challenged) would need to be able to explain how and why – and solely in health related terms, not public order – why a group of six friends can meet for an afternoon BBQ and stay outside long into the evening provided they remain ‘socially distanced’ (i.e. 2m apart, though this is not in the law, the Regulations, but only in the soft law Guidance) but a group of seven or eight political activists cannot hold a twenty minute vigil 2m apart on the steps of a Town Hall this weekend to mark the death of George Floyd in Mineapolis. That, to my mind, seems an indefensible distinction.