It feels a little like Christmas Eve today – anticipating what tomorrow will bring. For many though the Tory’s likely announcement of their plan for the Human Rights Act is going to resemble the revelation of an ill-fitting hand-knitted garish jumper, not the delights of a Breaking Bad boxset.

This short post is not going to be an encyclopaedic traverse of the terrain of domestic human rights protection. Instead though it seemed sensible to offer a couple of thoughts that could be borne in mind in the weeks and months of struggle ahead, as we make our way to May 2015. It is very unlikely to say anything new but – as we shall see – simple repetition is a tactic of opponents of the HRA, oftentimes of demonstrably untrue assertions, so if you can’t beat them…

First, though the plans have only been hinted at in recent months, it is clear the Tories want to rebalance the relationship between the UK and the Council of Europe/Strasbourg Court. One approach, floated by Chris Grayling over the weekend is that the “European Court of Human Rights will no longer be able to overrule British courts”. It is hard to see how this can happen. It is legally impossible for the Tories to legislate domestically to instruct an international supervisory court, and thus the other member states, how to approach cases that come before it. Grayling is blowing in the wind here, but what is symptomatic of the debate from the right, the truth – or legal reality – has long been the first casualty. In the same way, Westminster cannot pass a law revising the accepted meaning of use of lawful force under the UN Charter, and expect any other state to pay a blind bit of notice. UK courts of course would be required to do so – and perhaps this is what Grayling really meant, albeit that he tried to describe it in a legally illiterate manner. Doing so would mean that the UK – using that example – would have perhaps an entirely different definition or understanding of lawful force to any other. Using the HRA as our example, it would mean altering s.2 of the HRA. This is the option that Carl Gardner thinks will be announced tomorrow – and it has a long pedigree as a policy option, and not just on the right. Sadiq Khan has intimated the same approach for Labour, again (interestingly) in a Telegraph interview over the summer. There is something understandable to this but it is hard to see how it might be framed: the current wording was deliberately framed as not to bind British judges. Indeed a stronger adjuration was rejected. Yet judges have – or rather had – taken the view that s.2 in general required what has often been described as a mirror, that we mirror Strasbourg law so that UK law is no more, no less the same. Recent years have seen noticeable declarations of departure – we might think of Horncastle as a good example. The result there of failing to follow Strasbourg jurisprudence on admitting certain hearsay evidence was that in the next case to come before it, the ECtHR very clearly shifted position. In short what form of words can be latched upon to give this clear direction to judges?

That though is a soluble problem. It does however miss another counter: that the change in heart on the part of the European Court was the result of some form of inter-curial dialogue – and thus close involvement between the UK and Europe – something long advocated by Dominic Grieve as a strength of the current framework but, as Carl Gardner notes today, something that is both only long-term in result and unclaimable by an one party. It is therefore unpalatable in today’s “something must be done about human rights” politics. It also underplays, ignores, the very clear shift in the approach of the Strasbourg Court – far more deferential, far more of a subsidiary role in recent years respectful of and mindful towards elected representatives. This is reasonably well-documented, and we might think of Animal Defenders, von Hannover No 2 and this more recent case against the UK, the RMT decision from April this year. There, the UK’s ban on secondary industrial action was held not to violate article 11 and the Court said this (at [99])

In the sphere of social and economic policy, which must be taken to include a country’s industrial relations policy, the Court will generally respect the legislature’s policy choice unless it is “manifestly without reasonable foundation”. Moreover, the Court has recognised the “special weight” to be accorded to the role of the domestic policy-maker in matters of general policy on which opinions within a democratic society may reasonably differ widely The ban on secondary action has remained intact for over twenty years, notwithstanding two changes of government during that time. This denotes a democratic consensus in support of it, and an acceptance of the reasons for it, which span a broad spectrum of political opinion in the United Kingdom. These considerations lead the Court to conclude that in their assessment of how the broader public interest is best served in their country in the often charged political, social and economic context of industrial relations, the domestic legislative authorities relied on reasons that were both relevant and sufficient for the purposes of Article 11.

As I put it in an earlier UKCLA blog post in each “we can – if not clearly and explicitly – see the Court playing a political role, seeking to staunch national discontent with judgments would appear to be more politically welcome. This has simply been lost in the debate, and lost too with Grieve’s sacking. Is it coincidence that there was not one single newspaper report of the Government’s success in the RMT case?

Second, there is in essence something inherently duplicitous in the Tory’s approach: on one hand, the aim of reform and change is to “make the Supreme Court supreme” and on the other, stressing that this rebalancing will make the protection of human rights in the UK a more democratic endeavour, and thus something to be aspired to. You can either have judicial power or you can have democratic power – someone has the last word. Unless Grayling is also planning to tamper with the fundamental constitutional principle of Parliamentary Sovereignty – in which case many of us this week will urgently have to rewrite 1st year lecture handouts – the Supreme Court will not become sovereign. To configure it so that it has more sovereignty than Grayling considers it has now is again a legal falsity lost on a non-lawyer. It is not a divisible concept, certainly not something you can have more or less of. It is duplicitous too as – again as many have noted – without properly addressing the place of EU Law within the UK’s judicial order (and of course renegotiation, referendum and withdrawal are not unimaginable) whatever view we take of the ECHR, the human rights principles of the CJEU and the growing Charter jurisprudence mean that whatever is done in relationship to Strasbourg will offer a false dawn.

This post is not the place to go into the whys and wherefores of this debate – to which I & many, many others have contributed over the years. Here I agree with Gavin Phillipson: there is now an urgent need to debate and thrash around the appropriate constitutional balance between elected representatives and the judicial arm. We cannot avoid it. As he writes,

if we want to defend the ECHR as it is, we need to come up with clear arguments as to why the Strasbourg court should retain the final word on questions of human rights in Europe.

I would add just this – though this is not intended to be a Damescene moment: democracy is essentially majoritarian, that’s how it works. I often say to my undergraduate students, people like me – white, male middle aged, university educated professional, middle class – do not need rights. I can get MPs to do my dirty work for me if I need some sort of favour or special treatment. Minorities, by whatever description, by definition cannot – they simply cannot muster the power. If they could, they’d be a majority. Simplistic I accept – but a truth lurks. Human rights are about protecting often powerless people from the worst excesses of the exercise of political power by the rest. You cannot give greater protection by handing it all over, or back, to Parliament. This is not to accept that there is not a key role for Westminster, nor indeed for courts and judges – unravelling that is the next project for human rights constitutional lawyers – but simply to offer the view that tarting the proposals up in the language of democracy offers voters a misconceived view of what human rights are and should be about.

That does though make sense. The real thrust has been a media narrative of undesirables claiming rights – most often foreign criminals claiming the right to remain using Article 8. I have conducted my own empirical research (and blogged last week) and come to the conclusion that the extent of that is simply a fabrication. Readers of The Daily Mail – from the frequency with which stories are reported – would be under the impression that the success rate (i.e. those who manage not to be deported) is about 92%. Of 21 stories in that paper that were on foreign criminal deportations, 19 were about those in whose favour the courts had found. The reality is very different. Even the Mail itself has been reporting a success rate of a third – though using that to show a yearly 50% increase – while Home Office figures (admittedly for 2012) show a success rate for applicants of 24%. There is also a continual mantra linking “murderers and rapists” together – again, as I discovered, in 27 domestic human rights stories in the past year, almost all in the context of prisoners’ rights/deportation. It is easy to see a tsunami of moral panic building up, with such groups becoming the modern day folk devils, replacing Stan Cohen’s mods and rockers of the 1960s. This is reinforced – again as my research shows – by worthier victims (using the label applied by Herman and Chomsky in Manufacturing Consent) not needing to claim their human rights at all, or rather newspaper coverage simply omitting any mention of human rights as the reason for success in court. The successful claim by Beth Warren to use the sperm of her late husband “out of time” was based on her Article 8 right to family life yet readers of the Telegraph would have had no clue.

There is much more to the said about the HRA and its important place in our domestic order. David Green has quite properly been stressing Lord Bingham’s speech in which he rhetorically asks which of the many listed rights in the ECHR are its opponents against. It is, of course as is well-known, the product largely of British involvement though – to be fair – it would be an ill-conceived argument to focus solely on the very words of a document from 60 years ago, without even a nod to how those words have been interpreted. We could though, to take another Tory argument – that there is simply no authority for the expansion and development of the Convention, the living instrument approach point – as Nuala Mole did at a conference last week to the preamble of the ECHR

“Considering that the aim of the Council of Europe is the achievement of greater unity between its members and that one of the methods by which that aim is to be pursued is the maintenance and further realisation of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms” (my italics).

Instead, let us for now concentrate on what tomorrow brings and timeo Danaos et dona ferentes – beware Greeks bearing gifts.

My chapter builds on some previous work, contained in this book, published by Hart in 2015, but includes two novel aspects. First, it offers a semiotic, Barthesian decoding of the following, by now infamous, red top front page, noting the way the paper portrays human rights as something not currently of value for individuals like you and me – all those on the right of the picture, the silent majority, are identified by first names (and ages) to facilitate that assimilation – but as something that protects people who are distinguished only by some collective shared criminal identity, necessarily demarcating them as outsiders, as having rejected society and its norms.

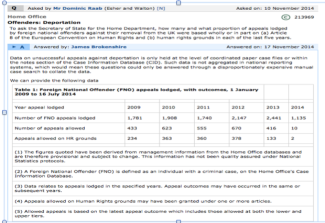

My chapter builds on some previous work, contained in this book, published by Hart in 2015, but includes two novel aspects. First, it offers a semiotic, Barthesian decoding of the following, by now infamous, red top front page, noting the way the paper portrays human rights as something not currently of value for individuals like you and me – all those on the right of the picture, the silent majority, are identified by first names (and ages) to facilitate that assimilation – but as something that protects people who are distinguished only by some collective shared criminal identity, necessarily demarcating them as outsiders, as having rejected society and its norms. Secondly, it discusses the results of an empirical content study that I conducted into coverage by the Daily Mail of one, hotly contested human rights issue: the (non-)deportation of foreign criminals, following conviction, on human rights grounds. Of 35 stories in the paper over a two-year period about named, identifiable individuals, just over 88% of them showed them being able to avoid deportation – a success rate for the Home Secretary of just over 11%. Official Home Office data for an overlapping three-year period (admittedly now several years ago) showed almost the opposite: on average, the Home Secretary succeeded in 81% of such cases: in only 19% of cases was the FNO (foreign national offender) able to remain in the UK. At the time the chapter was written, The Sun and the Daily Mail had a combined readership of 3.3m, and the Mail Online 14.3m hits. It is a massive problem, one on which I gave evidence to the JCHR over the summer as part of its “Enforcing Human Rights” inquiry since it is not a problem that can easily be solved by a regulator. It is not that the reporting is inaccurate or false – does it conform to independent records? – but is rather, as the communications theorist Dennis McQuail put it, one of completeness: are the facts sufficient to constitute an adequate account? The chapter includes further empirical research on the (non-) reporting of ECHR judgments, as well as discussion of various techniques of distortion that I identified in that earlier book. These are pre-emption (reporting cases too early in their life cycle but portraying them as establishing a binding ruling); prominence; partiality (in sources); and phrasing of stories, alongside three new ones: lies, damned lies and statistics; repetition for reinforcement; and what I term an Unverfremdungseffekt, a reversal of Bertolt Brecht dramaturgical ideas about alienation. The chapter concludes that “the least the HRA deserves is a clean fair fight – not one encumbered by misreporting, misconception, and the misconstruction of reality.”

Secondly, it discusses the results of an empirical content study that I conducted into coverage by the Daily Mail of one, hotly contested human rights issue: the (non-)deportation of foreign criminals, following conviction, on human rights grounds. Of 35 stories in the paper over a two-year period about named, identifiable individuals, just over 88% of them showed them being able to avoid deportation – a success rate for the Home Secretary of just over 11%. Official Home Office data for an overlapping three-year period (admittedly now several years ago) showed almost the opposite: on average, the Home Secretary succeeded in 81% of such cases: in only 19% of cases was the FNO (foreign national offender) able to remain in the UK. At the time the chapter was written, The Sun and the Daily Mail had a combined readership of 3.3m, and the Mail Online 14.3m hits. It is a massive problem, one on which I gave evidence to the JCHR over the summer as part of its “Enforcing Human Rights” inquiry since it is not a problem that can easily be solved by a regulator. It is not that the reporting is inaccurate or false – does it conform to independent records? – but is rather, as the communications theorist Dennis McQuail put it, one of completeness: are the facts sufficient to constitute an adequate account? The chapter includes further empirical research on the (non-) reporting of ECHR judgments, as well as discussion of various techniques of distortion that I identified in that earlier book. These are pre-emption (reporting cases too early in their life cycle but portraying them as establishing a binding ruling); prominence; partiality (in sources); and phrasing of stories, alongside three new ones: lies, damned lies and statistics; repetition for reinforcement; and what I term an Unverfremdungseffekt, a reversal of Bertolt Brecht dramaturgical ideas about alienation. The chapter concludes that “the least the HRA deserves is a clean fair fight – not one encumbered by misreporting, misconception, and the misconstruction of reality.”